.

Image: Allison/Adobe Stock; Ryan Pearce

Nearly 30 years ago, when Google launched the search engine that started its long march to dominance, its founders started without much hardware.

Known at first as Backrub and operated on the Stanford campus, the company’s first experimental server packed 40 gigabytes of data and was housed in a case made of Duplo blocks, the oversize version of Lego. Later, thanks to donations from IBM and Intel, the founders upgraded to a small server rack. In 2025, you can’t even fit Google search in a single data center, something that’s been true for a long time.

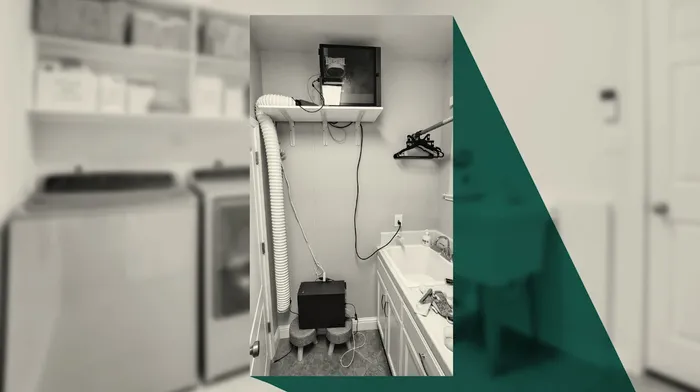

Still, with a little clever resourcing and a lot of work, you can get pretty close to a modern Google-esque experience using a machine roughly the size of that original Google server. You can even house it in your laundry room.

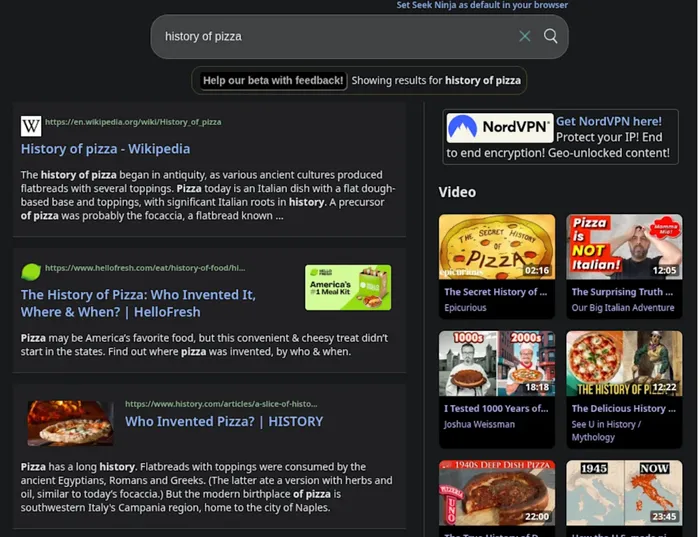

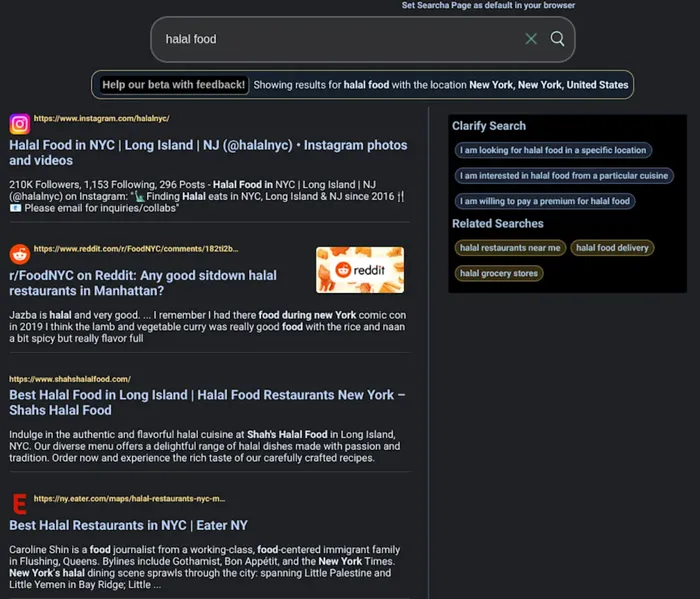

That’s where Ryan Pearce decided to put his new search engine, the robust Searcha Page, which has a privacy-focused variant called Seek Ninja. If you go to these web pages, you’re hitting a server next to Pearce’s washer and dryer. Not that you could tell from the search results.

“Right now, in the laundry room, I have more storage than Google in 2000 had,” Pearce says. “And that’s just insane to think about.”

.

Image: Courtesy of Ryan Pearce]

Why the laundry room? Two reasons: Heat and noise. Pearce’s server was initially in his bedroom, but the machine was so hot, it actually made it too uncomfortable to sleep. He has a separate bedroom from his wife because of sleep issues, but her prodding made him realise a relocation was necessary. So he moved it to the utility room, drilled in a route for a network cable to get through, and now, between clothes cycles, it’s where his search engines live. “The heat hasn’t been absolutely terrible, but if the door is closed for too long, it is a problem,” he says.

.

Image: Courtesy of Ryan Pearce

Other than a little slowdown in the search results (which, to Pearce’s credit, has improved dramatically over the past few weeks), you’d be hard-pressed to see where the gaps in his search engine lie. The results are often of higher quality than you might expect. That’s because Searcha Page and Seek Ninja are built around a massive database that’s 2 billion entries strong. “I’m expecting to probably be at 4 billion documents within a half year,” he says.

By comparison, the original Google, while still hosted at Stanford, had 24 million pages in its database in 1998, and 400 billion as of 2020—a fact revealed in 2023, during the United States v. Google LLC antitrust trial.

By current Google standards, 2 billion pages are a drop in the bucket. But it’s a pretty big bucket.

The scale that Pearce is working at is wild, especially given that he’s running it on what is essentially discarded server hardware. The secret to making it all happen? Large language models.

“What I’m doing is actually very traditional search,” Pearce says. “It’s what Google did probably 20 years ago, except the only tweak is that I do use AI to do keyword expansion and assist with the context understanding, which is the tough thing.”

Pearce’s search engines emphasize a minimalist look—and a desire for honest user feedback.

Image: Ryan Pearce

If you’re trying to avoid AI in your search, you might think, Hey, wait, is this actually what I want? But it’s worth keeping in mind that AI has often been a key part of our search DNA. Tools such as reverse image search, for example, couldn’t work without it. Long before we learned about glue on pizza, Google had been working to implement AI-driven context in more subtle ways, adding RankBrain to the mix about a decade ago. And in 2019, Microsoft executives told a search marketing conference that 90% of Bing’s search results came from machine learning—years before the search engine gained a chat window.

In many ways, the frustration many users have with LLMs may oversimplify the truth about AI’s role in search. It was already deeply embedded in modern search engines well before Google and Microsoft began to put it in the foreground.

And what we’re now learning is that AI is a great way to build and scale a search engine, even if you’re an army of one.

In many ways, Pearce is leaning into an idea that has picked up popular relevance in recent years: self-hosting. Many self-hosters might use a mini PC or a Raspberry Pi. But when you’re trying to build your own Google, you’re going to need a little more power than can fit in a tiny box.

Always curious about what it would be like to build a search engine himself, Pearce decided to actually do it recently, buying up a bunch of old server gear powerful enough to manage hundreds of concurrent sessions. It’s more powerful than some of Google’s early server setups.

“Miniaturisation has just made it so achievable,” he says.

Enabling this is a concept I like to call “upgrade arbitrage,” where extremely powerful old machines (particularly those targeting the workstation or server market) end up falling in price so significantly that it makes the gear attractive to bargain hunters. Many IT departments work around traditional upgrade cycles, usually around three years, meaning there’s a lot of old gear on the market. If buyers are willing to accept the added energy costs that come with the older gear, savvy gadget shoppers can get a lot of power for not a lot of up-front money.

The beefy CPU running this setup, a 32-core AMD EPYC 7532, underlines just how fast technology moves. At the time of its release in 2020, the processor alone would have cost more than $3,000. It can now be had on eBay for less than $200—and Pearce bought a quality control test version of the chip to further save money.

“I could have gotten another chip for the same price, which would have had twice as many threads, but it would have produced too much heat,” he says.

.

Image: .

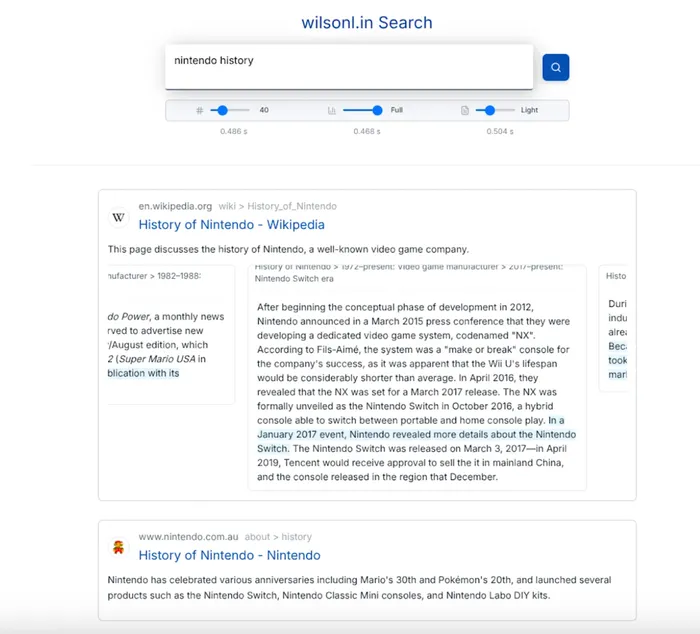

Wilson Lin’s cloud-based search engine, which uses a vector database, includes short summaries of every post produced by LLMs, which vary in length.

Image: .

What he built isn’t cheap—the system, all in, cost $5,000, with about $3,000 of that going toward storage—but it’s orders of magnitude less expensive than the hardware would have cost new. (Half a terabyte of RAM isn’t cheap, after all.) While there are certain off-site things that Pearce needs to lean on, the actual search engine itself is pulled in from this box. It’s bigger than a bread box, but a lot smaller than the cloud.

This is not how many developers approach complex software projects like this nowadays. Fellow ambitious hobbyist Wilson Lin, who on his personal blog recently described his efforts to create a search engine of his own, took the opposite approach from Pearce. He developed his own data parsing technologies to shrink the cost of running a search engine to pennies on the dollar compared to competing engines, leaning on at least nine separate cloud technologies.

“It’s a lot cheaper than [Amazon Web Services]—a significant amount,” Lin says. “And it gives me enough capacity to get somewhere with this project on a reasonable budget.”

Why are these developers able to get so close to what Google is building on relatively tight budgets and minimal hardware builds? Ironically, you can credit the technology many users blame for Google’s declining search quality—LLMs.

One of the biggest points of controversy around search engines is the overemphasis on artificial intelligence. Usually the result shows up in a front-facing way, by trying to explain your searches to you. Some people like the time savings. Some don’t. (Given that I built a popular hack for working around Google’s AI summaries, it might not surprise you to learn that I lean in the latter category.)

But when you’re attempting to build a dataset without a ton of outside resources, LLMs have proven an essential tool for reaching scale from a development and contextualization standpoint.

Pearce, who has a background in both enterprise software and game development, has not shied away from the programming opportunity that LLMs offer. What’s interesting about his model is that he’s essentially building the many parts that build up a traditional search engine, piecemeal. He estimates his codebase has around 150,000 lines of code at this juncture.

“And a lot of that is going back and reiterating,” he says. “If you really consider it, it’s probably like I’ve iterated over like 500,000 lines of code.”

Much of his iteration comes in the form of taking features initially managed by LLMs and writing them to work more traditionally. That’s created a design approach that allows him to build complex systems relatively quickly, and then iterate on what’s working.

“I think it’s definitely lowered the barrier,” Lin says of the LLM’s role in enabling DIY search engines. “To me, it seems like the only barrier to actually competing with Google, creating an alternate search engine, is not so much the technology, it’s mostly the market forces.”

Seek Ninja, the more private of Pearce’s two search engines, does not save your profile or use your location, making it a great incognito-mode option.

Image: .

The complexity of LLMs is such that it is one of the few things Pearce can’t implement on-site in his laundry room setup. Searcha Page and Seek Ninja instead use a service called SambaNova, which provides speedy access to the Llama 3 model at a low cost.

Annie Shea Weckesser, SambaNova’s CMO, notes that access to low-cost models is increasingly becoming essential for solo developers like Pearce, adding that the company is “giving developers the tools to run powerful AI models quickly and affordably, whether they’re working from a home setup or running in production.”

Pearce has other advantages that Sergey Brin and Larry Page didn’t have three decades ago when they founded Google, including access to the Common Crawl repository. That open repository of web data, an important (if controversial) enabler of generative AI, has made it easier for him to build his own crawler. Pearce says he was actually blocked from Common Crawl at one point as he built his moonshot.

“I really appreciate them. I wish I could give them back something, but maybe when I’m bigger,” he says. “It’s a really cool organization, and I want to be less dependent on them.”

There are places where Pearce has had to scale back his ambitions somewhat. For example, he initially thought he’d build his search engine using a vector database, which relies on algorithms to connect closely related items.

“But that completely bombed,” he says. “It was probably a lack of skill on my part. It did search, but . . . the results were very artistic, let’s say,” hinting at the fuzziness and hallucination that LLMs are known for.

Vector search, while complex, is certainly possible; that’s what Lin’s search engine uses, in the form of a self-created tool called CoreNN. That presents results differently from Pearce’s search engine, which works more like Google. Rather than using the meta descriptions most web pages have, it uses an LLM to briefly summarise the page itself and how it relates to the user’s search term.

“Once I actually started, I realised this is really deep,” Lin says of his project. “It’s not a single system, or you’re just focused on like a single part of programming. It’s like a lot of different areas, from machine learning and natural language processing, to how do you build an app that is smooth and low latency?”

Pearce’s Searcha Page is surprisingly adept at local searches, and can help find nearby food options quickly, based on your location.

Image: .

And then there’s the concept of doing a small-site search, along the lines of the noncommercial search engine Marginalia, which favours small sites over Big Tech. That was actually Pearce’s original idea, one that he hopes to get back to once he nails down the slightly broader approach he’s taken.

But there are already ideas emerging that weren’t even on Pearce’s radar.

“Someone from China actually reached out to me because . . . I think he wanted an uncensored search engine that he wanted to feed through his LLM, like his agent’s search,” he says.

It’s not realistic at this time for Pearce to expand beyond English—besides additional costs, it would essentially require him to build brand-new datasets. But such interest hints at the sheer power of his idea, which, based on its location, he can literally hear.

He does see a point where he moves the search engine outside his home—he’s a cloud-skeptic, so it would likely be to a colocation facility or similar type of data center. (Helping to pay for that future, he has started to dabble in some modest affiliate-style advertising, which tends to be less invasive than traditional banner ads.)

“My plan is if I get past a certain traffic amount, I am going to get hosted,” Pearce says. “It’s not going to be in that laundry room forever.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Ernie Smith is the editor of Tedium, a long-running newsletter that focuses on technology and offbeat history. Over his two-decade career, he has contributed to a wide variety of outlets, including Vice’s Motherboard, Atlas Obscura, and Fast Company.