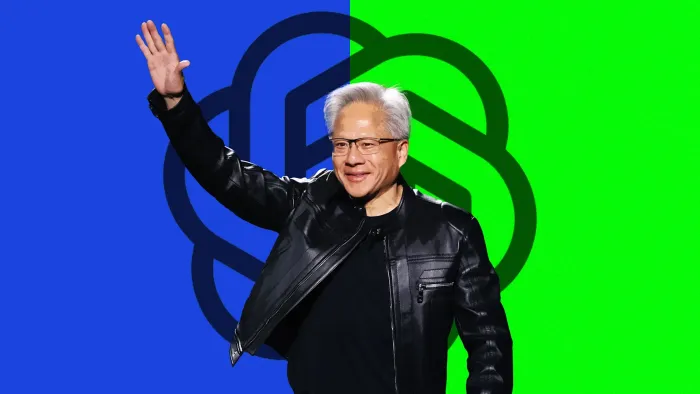

Co-founder and chief executive officer of Nvidia Corp., Jensen Huang

Image: Chesnot/Getty Images

Welcome to AI Decoded, Fast Company’s weekly newsletter that breaks down the most important news in the world of AI. I’m Mark Sullivan, a senior writer at Fast Company, covering emerging tech, AI, and tech policy.

This week, I’m focusing on the terms of Nvidia’s investment in OpenAI, in which the GPU maker gets guaranteed chip sales, an equity stake, and likely a product road map for years to come. I also look at the industry’s fixation on huge models and the quiet appeal of small ones.

Sign up to receive this newsletter every week via email here. And if you have comments on this issue and/or ideas for future ones, drop me a line at sullivan@fastcompany.com, and follow me on X (formerly Twitter) @thesullivan.

Now it’s all about data centres and electricity. Big Tech companies are promising that AI models and apps are about to revolutionise business, and executives like OpenAI CEO Sam Altman say the greatest barrier to that happening is a dearth of data centres to run the models that businesses will soon need to operate.

Big Tech companies are also challenged to find enough new energy sources to power and cool the massive data centres. Collectively, OpenAI, Amazon, Google, Meta, and Microsoft plan to spend more than $325 billion on data centres by the end of 2025, The New York Times reports. Anthropic said last year that it expects to spend $100 billion on these massive facilities over the next decade.

The tech companies are now racing to plan and finance the new data centres. And this is creating some unique arrangements. Nvidia announced Monday it will invest $100 billion in OpenAI, which will buy about 2% equity in the company. But OpenAI will likely use most of that money to buy Nvidia GPUs, or graphics processing units, the chips that represent the greatest single capital expenditure of building a data centre. “[T]hese investments might be circular and raise related party concerns, as Nvidia may own shares in a customer that will likely use such funds to buy more Nvidia gear,” writes Morningstar equity analyst Brian Colello in a research brief. (OpenAI struck a similar agreement with Microsoft when it took a $10 billion investment from the software giant, then used the money to buy its Azure cloud computing services.)

Notably, the Nvidia investment will time the release of the funds according to the pace at which OpenAI buys the chips: Nvidia gets guaranteed chip sales and a 2% share of OpenAI. (As Bryn Talkington, managing partner at Requisite Capital Management, told CNBC: “Nvidia invests $100 billion in OpenAI, which then OpenAI turns back and gives it back to Nvidia.”).

But it may be even better than that. Pitchbook AI and cybersecurity analyst Dimitri Zabelin believes Nvidia intends to plan the design of its future AI chips according to what it learns from OpenAI’s infrastructure scale-up.

That could be an invaluable feedback loop if all of the big AI companies follow OpenAI’s lead in scaling up its infrastructure and developing compute-intensive AI products. “Nvidia is consolidating control over the AI stack and reinforcing its position as the indispensable enabler of the sector’s next phase,” Zabelin says.

OpenAI will likely buy between 4 and 5 million of Nvidia’s new Vera Rubin GPUs, which will require 10 gigawatts of power to run. They will likely be installed within the five new data centres the company just announced as part of its Stargate Project (revealed at the White House with partners SoftBank, Oracle, and MGX). OpenAI now expects that Stargate will secure the full $500 billion in planned investment to build new data centres, and do so by the end of this year, ahead of schedule.

Right now, a huge portion of the total value of the stock market is held up by AI hope, the promise that AI will bring dramatic new efficiencies to the way business is done. Maybe businesses will grow more profitable by moving faster, or maybe they’ll do so by sloughing off human workers. Most likely both. The massive infrastructure investments of the Big Tech companies are all about supporting that transformation.

The companies building the gigantic data centres are frontier model companies; their products are huge, generalist models, like OpenAI’s GPT-5 and Google’s Gemini, that have trillions of parameters and are very expensive to train and operate. Generalist models are built to possess a wide array of knowledge—even a modicum of common sense about how the world works—that can be leveraged for all kinds of tasks.

They’re trained with massive amounts of diverse data and web content. It’s these frontier models that the AI companies hope will evolve to possess artificial general intelligence (AGI), or as much intelligence as most humans bring to most tasks, and then superintelligence, in which the model is far smarter than humans at almost any task.

But many of the analysts and researchers I’ve spoken to say that businesses usually need smaller models trained with a narrower set of (often proprietary) data that automate a specific set of tasks. They don’t need to power their apps with a gigantic (and expensive) model that knows about 15th-century gold coins and can write poetry.

Small models often don’t need to run inside a dedicated data centre, but are small enough to run on on-premise computers (in some cases, laptops or phones) or within a private cloud. With less exposure to wider networks, models that run on the edge devices are far less exposed to would-be hackers that might try to steal or poison corporate or personal data.

But OpenAI and Google aren’t selling that. They offer access to frontier models via application programming interfaces (APIs) to developers and corporations. And it’s the massive frontier models that carry the greatest risks for society-level harms, such as aiding in the building of a bioweapon or crashing economic systems.

Some have worried that putting so much intelligence and computing power together in one place could create a supercomputer smart enough to crack open every cryptocurrency wallet on the blockchain, which would cause economic chaos. Reducing the number of large frontier models (and tightly controlling their use) may be the only rational approach to protecting against the large-scale harms they might, in theory, inflict.

Currently, as the big AI companies like OpenAI, Anthropic, Google, and Meta quickly and dramatically scale up their data centres and models, we are trusting them to keep the models from being used for harm. Can private, profit-driven companies—some of which are under great pressure to get to profitability—control intelligences far greater than our own? Let’s hope so.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Mark Sullivan is a San Francisco-based senior writer at Fast Company who focuses on chronicling the advance of artificial intelligence and its effects on business and culture. He’s interviewed luminaries from the emerging space, including former Google CEO Eric Schmidt, Microsoft’s Mustafa Suleyman, and OpenAI’s Brad Lightcap.