.

Image: Avid Reader Press

The low point in Palantir’s very first quest for investors came during a pitch meeting in 2004 that CEO Alex Karp and some colleagues had with Sequoia Capital, which was arguably the most influential Silicon Valley VC firm. Sequoia had been an early investor in PayPal; its best-known partner, Michael Moritz, sat on the company’s board and was close to PayPal founder Peter Thiel, who had recently launched Palantir. But Sequoia proved no more receptive to Palantir than any of the other VCs that Karp and his team visited; according to Karp, Moritz spent most of the meeting absentmindedly doodling in his notepad.

Karp didn’t say anything at the time, but later wished that he had. “I should have told him to go fuck himself,” he says, referring to Moritz. But it wasn’t just Moritz who provoked Karp’s ire: the VC community’s lack of enthusiasm for Palantir made Karp contemptuous of professional investors in general. It became a grudge that he nurtured for years after.

.

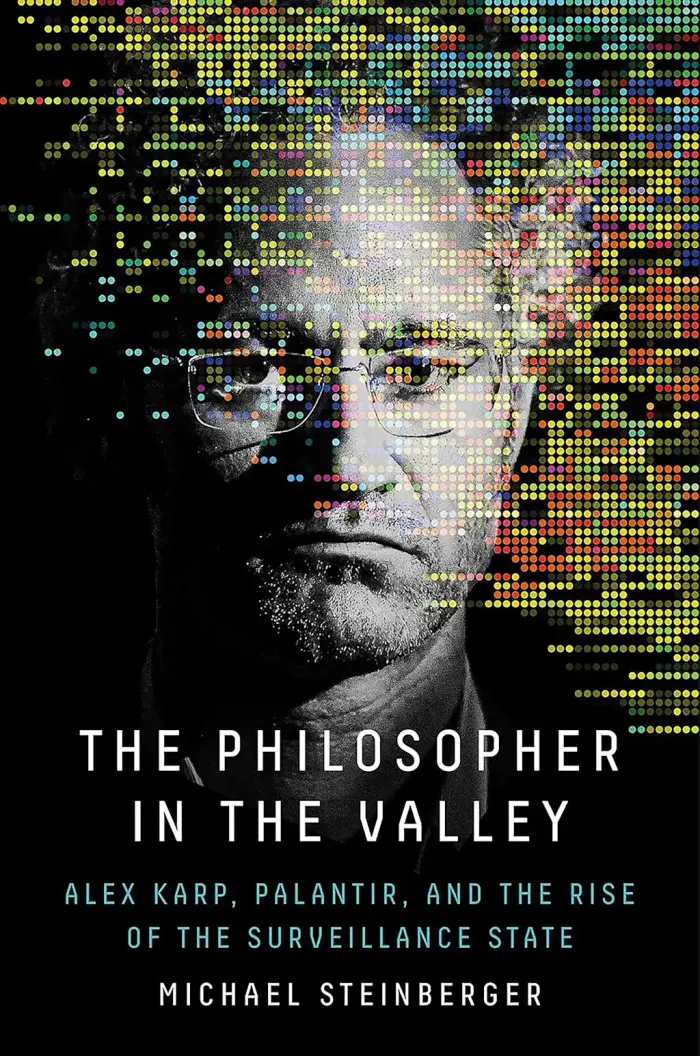

Image: Avid Reader Press

From The Philosopher in the Valley: Alex Karp, Palantir, and the Rise of the Surveillance State by Michael Steinberger. Copyright © 2025. Reprinted by permission of Avid Reader Press, an Imprint of Simon & Schuster Inc.

But the meetings on Sand Hill Road weren’t entirely fruitless. After listening to Karp’s pitch and politely declining to put any money into Palantir, a partner with one venture capital firm had a suggestion: if Palantir was really intent on working with the government, it could reach out to In-Q-Tel, the CIA’s venture capital arm. In-Q-Tel had been started a few years earlier, in 1999 (the name was a playful reference to “Q,” the technology guru in James Bond films). CIA Director George Tenet believed that establishing a quasi-public venture capital fund through which the agency could incubate start-ups would help ensure that the U.S. intelligence community retained a technological edge.

The CIA had been created in 1947 for the purpose of preventing another Pearl Harbor, and a half century on, its primary mission was still to prevent attacks on American soil. Two years after In-Q-Tel was founded, the country experienced another Pearl Harbor, the 9 ⁄ 11 terrorist attacks, a humiliating intelligence failure for the CIA and Tenet. At the time, In-Q-Tel was working out of a Virginia office complex known, ironically, as the Rosslyn Twin Towers, and from the twenty-ninth-floor office, employees had an unobstructed view of the burning Pentagon.

In-Q-Tel’s CEO was Gilman Louie, who had worked as a video game designer before being recruited by Tenet (Louie specialised in flight simulators; his were so realistic that they were used to help train Air National Guard pilots). Ordinarily, Louie did not take part in pitch meetings; he let his deputies do the initial screening. But because Thiel was involved, he made an exception for Palantir and sat in on its first meeting with In-Q-Tel.

What Karp and the other Palantirians didn’t know when they visited In-Q-Tel was that the CIA was in the market for new data analytics technology. At the time, the agency was mainly using a program called Analyst’s Notebook, which was manufactured by i2, a British company. According to Louie, Analyst’s Notebook had a good interface but had certain deficiencies when it came to data processing that limited its utility.

“We didn’t think their architecture would allow us to build next-generation capabilities,” Louie says.

Louie found Karp’s pitch impressive. “Alex presented well,” he recalls. “He was very articulate and very passionate.” As the conversation went on, Karp and his colleagues talked about IGOR, PayPal’s pioneering fraud-detection system, and how it had basically saved PayPal’s business, and it became apparent to Louie that they might just have the technical aptitude to deliver what he was looking for.

But he told them that the interface was vital—the software would need to organise and present information in a way that made sense for the analysts using it, and he described some of the features they would expect. Louie says that as soon as he brought this up, the Palantir crew “got out of sales mode and immediately switched into engineering solving mode” and began brainstorming in front of the In-Q-Tel team.

“That was what I wanted to see,” says Louie.

He sent them away with a homework assignment: he asked them to design an interface that could possibly appeal to intelligence analysts. On returning to Palo Alto, Stephen Cohen, one of Palantir’s co-founders, then 22 years old, and an ex-PayPal engineer named Nathan Gettings, sequestered themselves in a room and built a demo that included the elements that Louie had highlighted.

A few weeks later, the Palantirians returned to In-Q-Tel to show Louie and his colleagues what they had come up with. Louie was impressed by its intuitive logic and elegance. “If Palantir doesn’t work, you guys have a bright future designing video games,” he joked.

In-Q-Tel ended up investing $1.25 million in exchange for equity; with that vote of confidence, Thiel put up another $2.84 million. (In-Q-Tel did not get a board seat in return for its investment; even after Palantir began attracting significant outside money, the company never gave up a board seat, which was unusual, and to its great advantage.)

Karp says the most beneficial aspect of In-Q-Tel’s investment was not the money but the access that it gave Palantir to the CIA analysts who were its intended customers. Louie believed that the only way to determine whether Palantir could really help the CIA was to embed Palantir engineers in the agency; to build software that was actually useful, the Palantirians needed to see for themselves how the analysts operated. “A machine is not going to understand your workflows,” Louie says. “That’s a human function, not a machine function.”

The other reason for embedding the engineers was that it would expedite the process of figuring out whether Palantir could, in fact, be helpful. If the CIA analysts didn’t think Palantir was capable of giving them what they needed, they were going to quickly let their superiors know. “We were at war,” says Louie, “and people did not have time to waste.”

Louie had the Palantir team assigned to the CIA’s terrorism finance desk. There they would be exposed to large data sets, and also to data collected by financial institutions as well as the CIA. This would be a good test of whether Karp and his colleagues could deliver: tracking the flow of money was going to be critical to disrupting future terrorist plots, and it was exactly the kind of task that the software would have to perform in order to be of use to the intelligence community.

But Louie also had another motive: although Karp and Thiel were focused on working with the government, Louie thought that Palantir’s technology, if it proved viable, could have applications outside the realm of national security, and if the company hoped to attract future investors, it would ultimately need to develop a strong commercial business.

Stephen Cohen and engineer Aki Jain worked directly with the CIA analysts. Both had to obtain security clearance, and over time, numerous other Palantirians would do the same. Some, however, refused—they worried about Big Brother, or they didn’t want the FBI combing through their financial records, or they enjoyed smoking pot and didn’t want to give it up. Karp was one of the refuseniks, as was Joshua Goldenberg, the head of design. Goldenberg says there were times when engineers working on classified projects needed his help. But because they couldn’t share certain information with him, they would resort to hypotheticals.

As Goldenberg recalls, “Someone might say, ‘Imagine there’s a jewel thief and he’s stolen a diamond, and he’s now in a city and we have people following him—what would that look like? What tools would you need to be able to do that?’”

Starting in 2005, Cohen and Jain traveled on a biweekly basis from Palo Alto to the CIA’s headquarters in Langley, Virginia. In all, they made the trip roughly two hundred times. They became so familiar at the CIA that analysts there nicknamed Cohen “Two Weeks.” The Palantir duo would bring with them the latest version of the software, the analysts would test it out and offer feedback, and Cohen and Jain would return to California, where they and the rest of the team would address whatever problems had been identified and make other tweaks. In working side by side with the analysts, Cohen and Jain were pioneering a role that would become one of Palantir’s signatures.

It turned out that dispatching software engineers to job sites was a shrewd strategy—it was a way of discovering what clients really needed in the way of technological help, of developing new features that could possibly be of use to other customers, and of building relationships that might lead to additional business within an organisation. The forward-deployed engineers, as they came to be called, proved to be almost as essential to Palantir’s eventual success as the software itself. But it was that original deployment to the CIA, and the iterative process that it spawned, that enabled Palantir to successfully build Gotham, its first software platform.

Ari Gesher, an engineer who was hired in 2005, says that from a technology standpoint, Palantir was pursuing a very ambitious goal. Some software companies specialise in front-end products—the stuff you see on your screen. Others focused on the back-end, the processing functions. Palantir, says Gesher, “understood that you needed to do deep investments in both to generate outcomes for users.”

According to Gesher, Palantir also stood apart in that it aimed to be both a product company as well as a service company. Most software makers were one or the other: they either custom-built software, or they sold off-the-shelf products that could not be tailored to the specific needs of a client. Palantir was building an off-the-shelf product that could also be customised.

Despite his lack of technical training—or, perhaps, because of it—Karp had also come up with a novel idea for addressing worries about civil liberties: he asked the engineers to build privacy controls into the software. Gotham was ultimately equipped … with two guardrails—users were able to access only information that they were authorised to view, and the platform generated an audit trail that indicated if someone tried to obtain material off-limits to them. Karp liked to call it a “Hegelian” remedy to the challenge of balancing public safety and civil liberties, a synthesis of seemingly unreconcilable objectives. As he told Charlie Rose during an interview in 2009, “It is the ultimate Silicon Valley solution: you remove the contradiction, and we all march forward.”

In the end, it took Palantir around three years, lots of setbacks, and a couple of near-death experiences to develop a marketable software platform that met these parameters.

“There were moments where we were like, ‘Is this ever going to see the light of day?’” Gesher says. The work was arduous, and there were times when the money ran short. A few key people grew frustrated and talked of quitting.

Palantir also struggled to win converts at the CIA. Even though In-Q-Tel was backing Palantir, analysts were not obliged to switch to the company’s software, and some who tried it were underwhelmed.

But in what would become another pattern in Palantir’s rise, one analyst was not just won over by the technology; she turned into a kind of in-house evangelist on Palantir’s behalf. Sarah Adams discovered Palantir not at Langley, but rather on a visit to Silicon Valley in late 2006. Adams worked on counterterrorism, as well, but in a different section. She joined a group of CIA analysts at a conference in the Bay Area devoted to emerging technologies. Palantir was one of the vendors, and Stephen Cohen demoed its software. Adams was intrigued by what she saw, exchanged contact information with Cohen, and upon returning to Langley asked her boss if her unit could do a pilot program with Palantir. He signed off on it, and a few months later, Adams and her colleagues were using Palantir’s software.

Adams says that the first thing that jumped out at her was the speed with which Palantir churned data. “We were a fast-moving shop; we were kind of the point of the spear, and we needed faster analytics,” she says.

According to Adams, Palantir’s software also had a “smartness” that Analyst’s Notebook lacked. It wasn’t just better at unearthing connections; even its basic search function was superior. Often, names would be misspelled in reports, or phone numbers would be written in different formats (dashes between numbers, no dashes between numbers). If Adams typed in “David Petraeus,” Palantir’s search engine would bring up all the available references to him, including ones where his name had been incorrectly spelled. This ensured that she wasn’t deprived of possibly important information simply because another analyst or a source in the field didn’t know that it was “Petraeus.”

Beyond that, Palantir’s software just seemed to reflect an understanding of how Adams and other analysts did their jobs—the kind of questions they were seeking to answer, and how they wanted the answers presented. She says that Palantir “made my job a thousand times easier. It made a huge difference.”

Her advocacy was instrumental in Palantir securing a contract with the CIA. Similar stories would play out in later deployments—one employee would end up championing Palantir, and that person’s proselytizing would eventually lead to a deal.

But the CIA was the breakthrough: it was proof that Palantir had developed software that really worked, and also the realization of the ambition that had brought the company into being. Palantir had been founded by Peter Thiel for the purpose of assisting the U.S. government in the war on terrorism, and now the CIA had formally enlisted its help in that battle.

Palantir’s foray into domestic law enforcement was an extension of its counterterrorism work. In 2007, the New York City Police Department’s intelligence unit began a pilot program using Palantir’s software. Before 9/11, the intelligence division had primarily focused on crime syndicates and narcotics. But its mandate changed after the terrorist attacks. The city tapped David Cohen, a CIA veteran who had served as the agency’s deputy director of operations, to run the unit, and with the city’s blessing, he turned it into a full-fledged intelligence service employing some one thousand officers and analysts. Several dozen members of the team were posted overseas, in cities including Tel Aviv, Amman, Abu Dhabi, Singapore, London, and Paris.

“The rationale for the N.Y.P.D.’s transformation after September 11th had two distinct facets,” The New Yorker’s William Finnegan wrote in 2005. “On the one hand, expanding its mission to include terrorism prevention made obvious sense. On the other, there was a strong feeling that federal agencies had let down New York City, and that the city should no longer count on the Feds for its protection.” Finnegan noted that the NYPD was encroaching on areas normally reserved for the FBI and the CIA but that the federal agencies had “silently acknowledged New York’s right to take extraordinary defensive measures.”

Cohen became familiar with Palantir while he was still with the CIA, and he decided that the company’s software could be of help to the intelligence unit. In what was becoming a familiar refrain, there was internal resistance. “For the average cops, it was just too complicated,” says Brian Schimpf, one of the first forward-deployed engineers assigned to the NYPD.

“They’d be like, ‘I just need to look up license plates, bro; I don’t need to be doing these crazy analytical processes.’” IBM’s technology was the de facto incumbent at the NYPD, which also made it hard to convert people.

Another stumbling block was price: Palantir was expensive, and while the NYPD had an ample budget, not everyone thought it was worth the investment. But the software caught on with some analysts, and over time, what began as a counter terrorism deployment moved into other areas, such as gang violence.

This mission creep was something that privacy advocates and civil libertarians anticipated. Their foremost worry, in the aftermath of 9/11, was that innocent people would be ensnared as the government turned to mass surveillance to prevent future attacks, and the NSA scandal proved that these concerns were warranted.

But another fear was that tools and tactics used to prosecute the war on terrorism would eventually be turned on Americans themselves. The increased militarization of police departments showed that “defending the homeland” had indeed morphed into something more than just an effort to thwart jihadis. Likewise, police departments also began to use advanced surveillance technology.

Andrew Guthrie Ferguson, a professor of law at George Washington University who has written extensively about policing and technology, says that capabilities that had been developed to meet the terrorism threat were now “being redirected on the domestic population.”

Palantir was part of this trend. In addition to its work with the NYPD, it provided its software to the Cook County Sheriff’s Office (a relationship that was part of a broader engagement with the city and that would dissolve in controversy). However, it attracted much of its police business in its own backyard, California. The Long Beach and Burbank Police Departments used Palantir, as did sheriff departments in Los Angeles and Sacramento counties. The company’s technology was also used by several Fusion Centers in California—these were regional intelligence bureaus established after 9/11 to foster closer collaboration between federal agencies and state and local law enforcement. The focus was on countering terrorism and other criminal activities.

But Palantir’s most extensive and longest-lasting law enforcement contract was with the Los Angeles Police Department. It was a relationship that began in 2009. The LAPD was looking for software that could improve situational awareness for officers in the field—that could allow them to quickly access information about, say, a suspect or about previous criminal activity on a particular street. Palantir’s technology soon became a general investigative tool for the LAPD.

The department also started using Palantir for a crime-prevention initiative called LASER. The goal was to identify “hot spots”—streets and neighborhoods that experienced a lot of gun violence and other crimes. The police would then put more patrols in those places. As part of the stepped-up policing, officers would submit information about people they had stopped in high-crime districts to a Chronic Offenders Bulletin, which flagged individuals whom the LAPD thought were likely to be repeat offenders.

This was predictive policing, a controversial practice in which quantitative analysis is used to pinpoint areas prone to crime and individuals who are likely to commit or fall victim to crimes. To critics, predictive policing is something straight out of the Tom Cruise thriller Minority Report, in which psychics identify murderers before they kill, but even more insidious. They believe that data-driven policing reinforces biases that have long plagued America’s criminal justice system and inevitably leads to racial profiling.

Karp was unmoved by that argument. In his judgment, crime was crime, and if it could be prevented or reduced through the use of data, that was a net plus for society. Blacks and Latinos, no less than whites, wanted to live in safe communities. And for Karp, the same logic that guided Palantir’s counterterrorism work applied to its efforts in law enforcement—people needed to feel safe in their homes and on their streets, and if they didn’t, they would embrace hard-line politicians who would have no qualms about trampling on civil liberties to give the public the security it demanded. Palantir’s software, at least as Karp saw it, was a mechanism for delivering that security without sacrificing privacy and other personal freedoms.

However, community activists in Los Angeles took a different view of Palantir and the kind of police work that the company was enabling. An organization called the Stop LAPD Spying Coalition organized protests and also published studies highlighting what it claimed was algorithmic-driven harassment of predominantly black and Latino neighborhoods and of people of color. LASER, it said, amounted to a “racist feedback loop.” In the face of criticism, the LAPD grew increasingly sensitive about its predictive policing efforts and its ties to Palantir.

To Karp, the fracas over Palantir’s police contracts was emblematic of what he saw as the left’s descent into mindless dogmatism. He said that many liberals now seemed “to reject quantification of any kind. And I don’t understand how being anti-quantitative is in any way progressive.”

Karp said that he was actually the true progressive. “If you are championing an ideology whose logical consequence is that thousands and thousands and thousands of people over time that you claim to defend are killed, maimed, go to prison—how is what I’m saying not progressive when what you are saying is going to lead to a cycle of poverty?”

He conceded, though, that partnering with local law enforcement, at least in the United States, was just too complicated. “Police departments are hard because you have an overlay of legitimate ethical concerns,” Karp said. “I would also say there is a politicization of legitimate ethical issues to the detriment of the poorest members of our urban environments.”

He acknowledged, too, that the payoff from police work wasn’t enough to justify the agita that came with it. And in truth, there hadn’t been much of a payoff; indeed, Palantir’s technology was no longer being used by any U.S. police departments. The New York City Police Department had terminated its contract with Palantir in 2017 and replaced the company’s software with its own data analysis tool. In 2021, the Los Angeles Police Department had ended its relationship with Palantir, partly in response to growing public pressure. So had the city of New Orleans, after an investigation by The Verge caused an uproar.

But Palantir still had contracts with police departments in several European countries. And since 2014, Palantir’s software has been used in domestic operations by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, work that has expanded under the second Trump administration, and earned criticism from a number of former employees.

In 2019, when I was working on my story about Palantir for The New York Times Magazine, I tried to meet with LAPD officials to talk about the company’s software, but they declined. Six years earlier, however, a Princeton doctoral candidate named Sarah Brayne, who was researching the use of new technologies by police departments, was given remarkable access to the LAPD. She found that Palantir’s platform was used extensively—more than one thousand LAPD employees had access to the software—and was taking in and merging a wide range of data, from phone numbers to field interview cards (filed by police every time they made a stop) to images culled from automatic license plate readers, or ALPRs.

Through Palantir, the LAPD could also tap into databases of police departments in other jurisdictions, as well as those of the California state police. In addition, they could pull up material that was completely unrelated to criminal justice—social media posts, foreclosure notices, utility bills.

Via Palantir, the LAPD could obtain a trove of personal information. Not only that: through the network analysis that the software performed, the police could identify a person of interest’s family members, friends, colleagues, associates, and other relations, putting all of them in the LAPD’s purview. It was a virtual dragnet, a point made clear by one detective who spoke to Brayne.

“Let’s say I have something going on with the medical marijuana clinics where they’re getting robbed,” he said. “I can put in an alert to Palantir that says anything that has to do with medical marijuana plus robbery plus male, black, six foot.” He readily acknowledged that these searches could just be fishing expeditions and even used a fishing metaphor. “I like throwing the net out there, you know?” he said.

Brayne’s research showed the potential for abuse. It was easy, for instance, to conjure nightmare scenarios involving ALPR data. A detective could discover that a reluctant witness was having an affair and use that information to coerce his testimony. There was also the risk of misconduct outside the line of duty—an unscrupulous analyst could conceivably use Palantir’s software to keep tabs on his ex-wife’s comings and goings. Beyond that, millions of innocent people were unknowingly being pulled “into the system” simply by driving their cars.

When I spoke to Brayne, she told me that what most troubled her about the LAPD’s work with Palantir was the opaqueness.

“Digital surveillance is invisible,” she said. “How are you supposed to hold an institution accountable when you don’t know what they are doing?”

Adapted from The Philosopher in the Valley: Alex Karp, Palantir, and the Rise of the Surveillance State by Michael Steinberger. Copyright © 2025. Reprinted by permission of Avid Reader Press, an Imprint of Simon & Schuster Inc.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Michael Steinberger is a contributing writer for The New York Times Magazine and the author of The Philosopher in the Valley, Au Revoir to All That, and The Wine Savant.