.

Image: Courtesy The New York Times

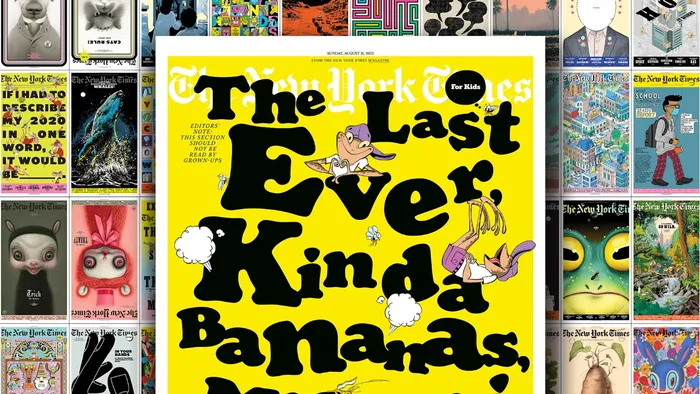

The New York Times made $455 million in profit last year. Unfortunately, that was not quite enough to save its award-winning kids section. On Sunday, the New York Times for Kids released its final monthly insert—its last issue after eight years and nearly 100 issues of publishing.

Its staff, which had been quietly reduced from roughly a dozen people to half that over the years, have received new positions inside the company. An insider says the shift is a way of investing more resources into New York Times Magazine (which Kids fell under), as the publication plans to have a more significant digital presence.

“We have new priorities now that force us to make some tough decisions about where to commit resources,” says New York Times Magazine editor-in-chief Jake Silverstein.

But the decision to kill a rare, analog piece of publishing—in an era when parents are looking for resources for their children to unplug—seems remarkably short-sighted.

August 2025. Illustration by Zohar Lazar.

Image: Courtesy The New York Times

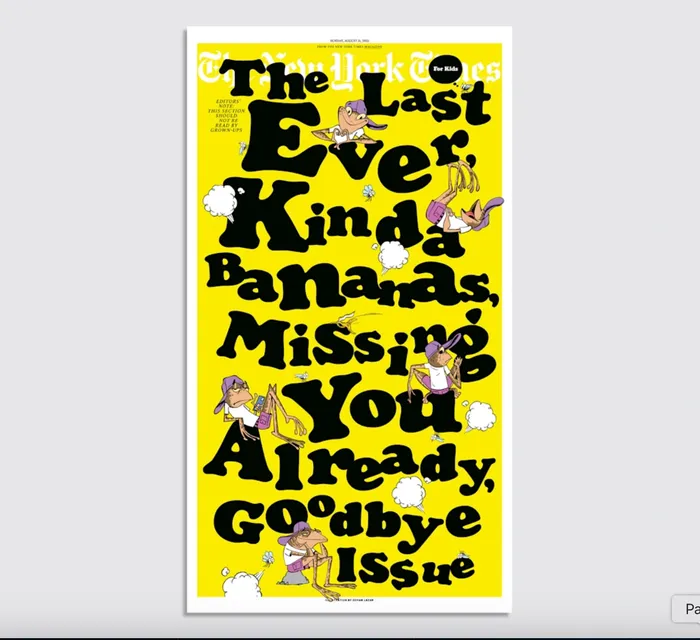

In 2016, Caitlin Roper found herself in the newsroom face-to-face with a tough critic. He’d just listened to her lineup for the Times’ new Kids section she was planning. It wouldn’t talk down to children, she explained. It would have international news, how-tos, and stories about style. But it would also be delightful, with rich magazine illustrations blown up to the poster-scale of a newspaper broadsheet.

Her critic wasn’t some grizzled editor with red ink-stained fingers. It was the 13-year-old son of a colleague. Upon hearing the full lineup of inaugural stories, he said, solemnly, “You should have a story about slime.”

May 2017. Illustration by Kelsey Dake.

Image: Courtesy The New York Times]

Roper knew he was right. Slime would get really big. And the young man scored his first writing assignment.

“That wasn’t the point of a kids section—to create a place in the Times to publish children—but [it was a goal to] have kids voices in every issue and story,” says Roper. “For a story about flooding, we’d interview young people affected by the flood.”

It’s just one example of how Roper—who co-founded the section alongside design director Deborah Bishop—and her team were solving some of the biggest shortcomings of children’s publishing.

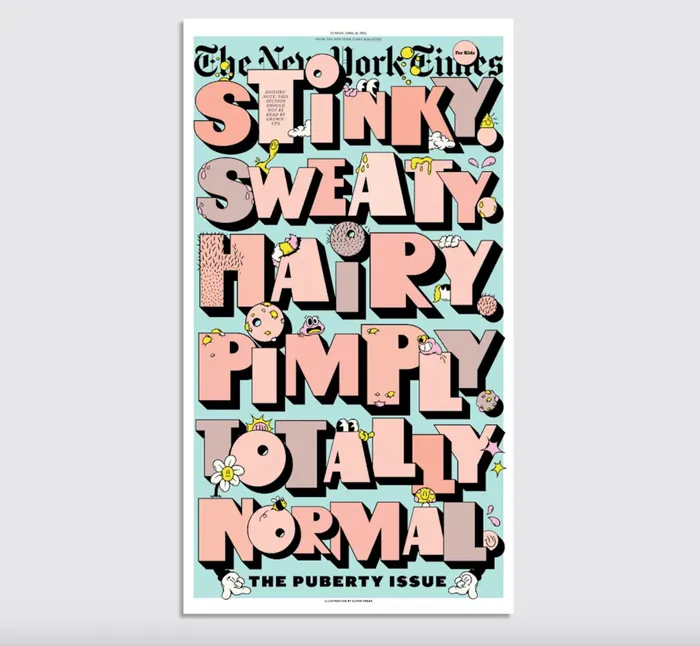

April 2023. Illustration by Super Frank. [Image: courtesy The New York Times]

Image: Courtesy The New York Times

Roper came from Wired. Bishop had done a stint at Martha Stewart Magazine, and Martha Stewart Kids. They knew that quality children’s publications were few and far between. These magazines are often designed less for kids than they are for adults. In some cases, that means they become superficial art projects that lack any substance. In others, they are insultingly pedantic.

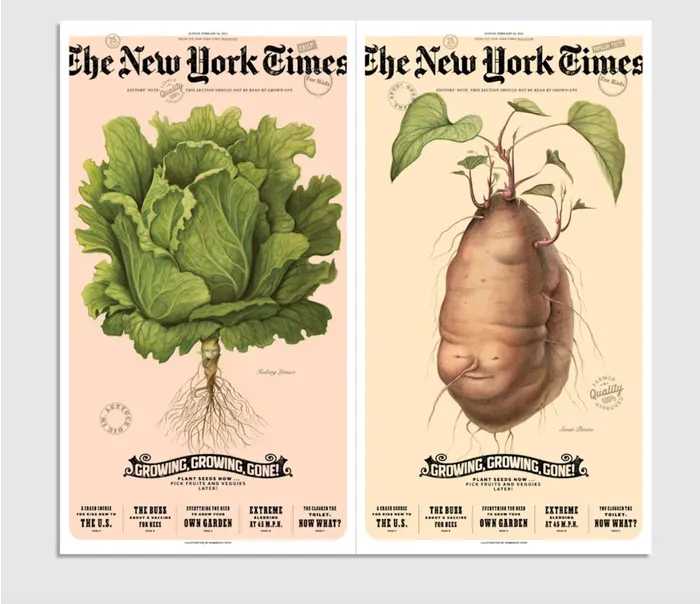

Feb 2023. Illustration by Armando Veve.

Image: Courtesy The New York Times

“People who don’t understand design don’t get that, but you can talk down visually…and frankly that’s what I hated about kids magazines,” says Roper, describing a tropeish language of photos and starburst graphics. “‘Here’s a naked mole rat! It has 763 wrinkles!’ And that’s the whole story.”

Roper and Bishop were given significant latitude from Silverstein. “His brief to me was…it’s not a magazine. And it’s not a newspaper. You’re somewhere right in the middle,” recalls Bishop. “It was a great idea because, right off the mark, we were innovating…and much less siloed than the newspaper.”

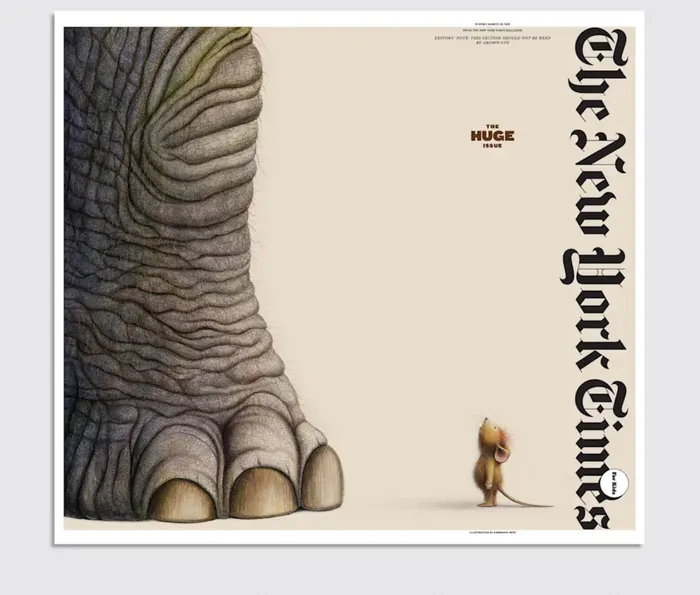

March 2025. Illustration by Armando Veve.

Image: Courtesy The New York Times

As Bishop explains, the canvas of the full newspaper offered her incredible scale—the front page was an illustration the size of a poster. (And in the case of the body issue, the edition featured a full “panel eight” fold out, so kids could place a huge anatomical model on their wall.) The penchant for illustration was creative, but also respectful of budgets. Illustrators tend to be cheaper to hire than photographers.

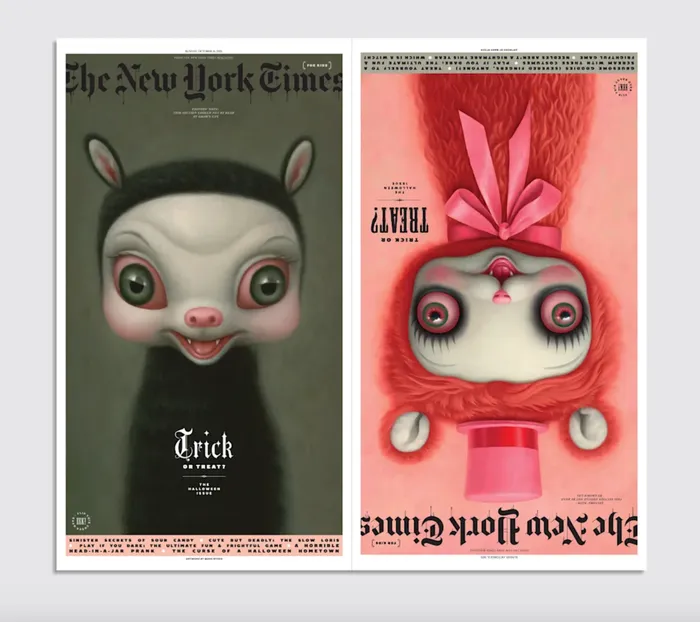

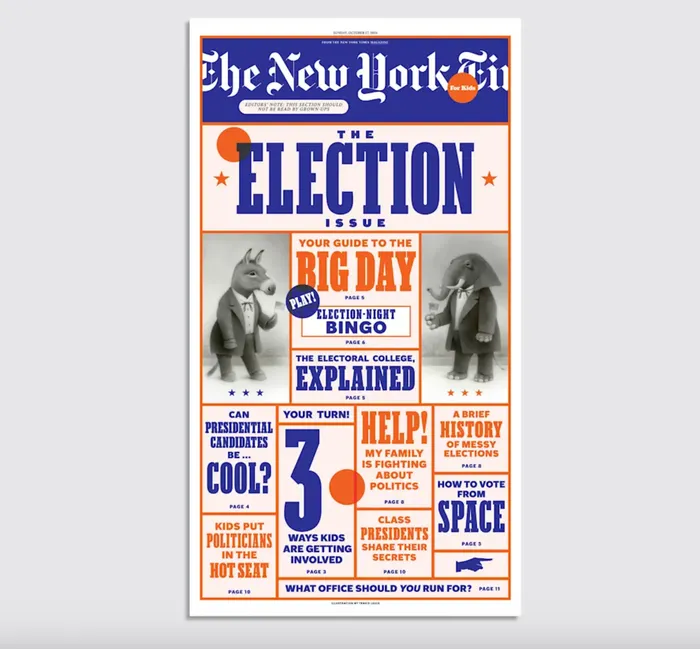

Up top, each cover set the tone by heading the paper’s classic logo. Sometimes the logo might be presented stoically, other times, covered in popcorn or dripping with goo. In all cases, designers added a cheeky “for kids” (this add-on might be held by an octopus), as part of an implied irreverence meant to channel hints of MAD Magazine and old monster cards.

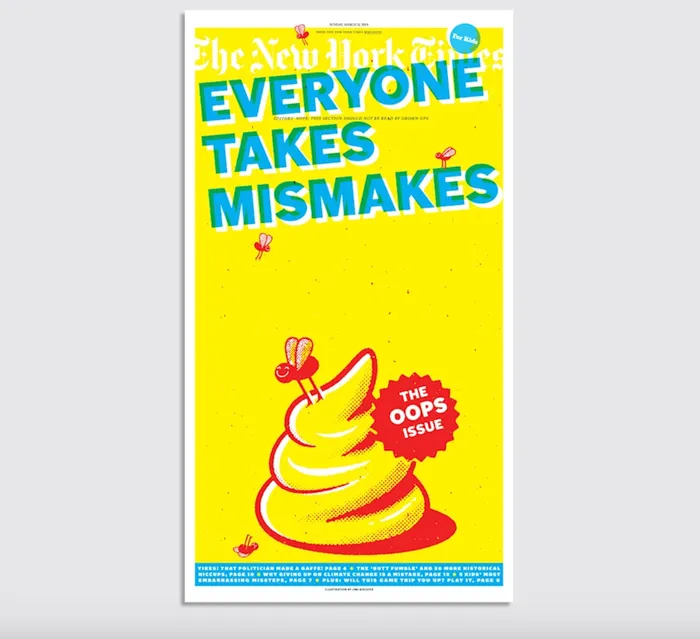

March 2024. Illustration by Jimi Biscuits.

Image: Courtesy The New York Times

“I think that’s exactly what it needed for smart kids,” says Bishop. Then inside, the story selection matched its amusing but intellectual ambitions.

In one edition—celebrating the battle of cats vs dogs—it featured a cat cover and cat stories. But flip the paper over, and it featured a dog cover and dog stories. Stories of scientific research essentially met in a fight in the middle. Even though the style was joyous, and often animal-filled (kids love animals), the Times’s own journalists still penned stories for children on topics like blockchain and January 6. It featured an interview with two children who survived a school shooting.

“There’s so much visual delight in the section but also not a fear of engaging with real stories,” says Roper.

Oct 2021. Artwork by Mark Ryden.

Image: Courtesy The New York Times

New York Times for Kids first launched as a one-off issue, a gift for subscribers to the print edition of the Times. After a lauded reception, it became a monthly product.

“Part of the idea was, could we do more innovation in print?” Roper recalls. It followed a string of experiments from the Times like a cardboard AR headset made with Google, and other one-off projects like a quiz-filled Puzzlemania. But while excellent as a value-add for print subscribers, there’s no doubt that in 2016, publishing more stuff in analog form didn’t exactly feel like the future in a world trending toward video and social media.

Over the years, the Times explored how its Kids section might scale. Could it sell subscriptions directly to schools? It also worked on its own digitization. The section built a successful Instagram page, and it also spent around two years creating a full New York for Times for Kids app, similar to how it built standalone apps for Cooking and Games.

The paper at large has remained ahead of the curve in part through its deep investments into digital platforms—it just launched a fully overhauled app last year. The Kids app envisioned how-tos and weekly activities for families, but the project was shut down as the Times prioritized other projects.

The Kids staff was alerted just last month that the section would fold, and the general response has been a feeling of abandonment from the greater Times machine. A team of journalists created a beloved product that was never fully promoted by the Times to fulfill an expanded reach or monetization.

Oct 2024. Illustration by Travis Louie.

Image: Courtesy The New York Times

It’s no secret that journalism is struggling. The last 20 years has represented a mass extinction event for publishers as the tech industry has stolen the public’s attention and gamified engagement at the expense of truth. Since 2002, 75% of local journalists have been wiped out in this transition.

But the big have still gotten bigger in this environment. Companies like the NYT are among the only remaining power brokers in “legacy” media—those with the growing subscription revenue that can weather the storms of fickle algorithms and afford to publish culturally valuable projects, even if individually some of them may appear to operate at a loss.

June 2019. Illustration by Alëna Skarina.

Image: Courtesy The New York Times

The company claims that it will pursue “other opportunities to serve younger audiences in the future.” But the New York Times for Kids was a love letter to the craft of analog publishing. It was a gateway to getting children interested in the greater world. And it was, quite simply, quality media for a demographic that’s already losing PBS and will otherwise learn about the world through social feeds.

There was and is a market for the New York Times for Kids—I say as a parent with two kids I’m working to keep interested in a world beyond screens. It just seems that pursuing this market wasn’t worth the trouble of a highly profitable publicly traded corporation.

The current slogan of the NYT is, “It’s your world to understand.” For children, perhaps I might suggest the modifier, “on your own.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Mark Wilson is the global design editor at Fast Company, who covers the entirety of design’s impact on culture and business.. An authority in product design, UX, AI, experience design, retail, food, and branding, he has reported landmark features on companies ranging from Nike and Google to MSCHF, Canva, Samsung, Snap, IDEO, and Target, while profiling design luminaries including Tyler the Creator, Jony Ive, and Salehe Bembury.