.

Image: Google

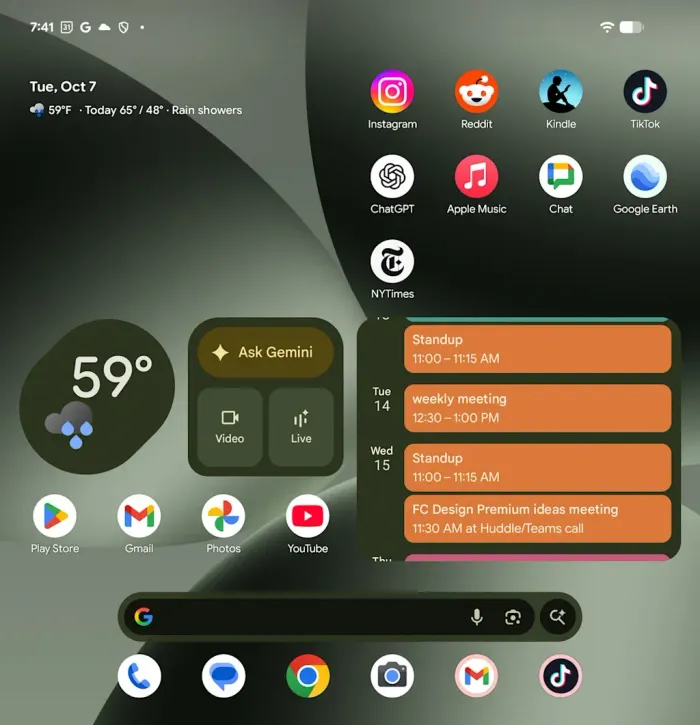

Up until a week ago, I was really quite satisfied by my iPhone 17 Pro. Not the Liquid Glass, but its soft orange aluminum frame felt just new enough to give me a spark.

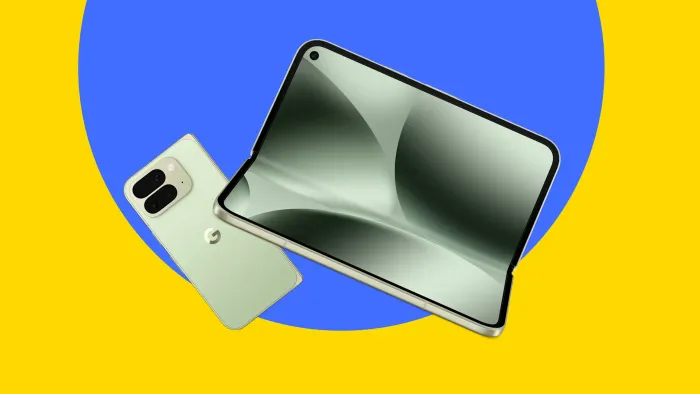

Then I opened the Google Pixel 10 Pro Fold. Yes, its name is too long. Yes, it costs $700 more than my iPhone. Yes, it’s still heavier than I want it to be. And yet, I hate to admit it . . . the Fold justifies every analyst who has cried that Apple’s hesitance to adopt flexible screen technologies is starting to make it look dated.

An estimated 17 million folding smartphones sold last year, representing a scant 1.5% of the smartphone market, but about every analyst expects that figure to balloon in the next few years. I believe that trajectory could prove out, but I still see the market going either way—it will come down to if the technology can keep iterating toward a sweet spot that turns the tech into delectable design.

.

Image: Google

Folding phones began as a gimmick deployed by a smartphone industry that’s satisfied their customers too well. There’s simply not much reason to upgrade your phone, ever, unless you’ve broken it. But that doesn’t mean they’ll always be silly.

After all, we’ve rolled up scrolls and folded maps and letters for centuries. It’s just a natural way to convert a large 2D object into a more portable one. But they’ve definitely felt a bit futile, given that their thickness and weight offset any value of space savings. (Do you really want to unfold a brick into a thinner brick?)

In the meantime, here’s a no-nonsense take on what it’s really like to use the current state of the art in folding phones—with thoughts from Google’s own development team on how it’s approaching the challenge, and possibilities, ahead.

.

Image: Google

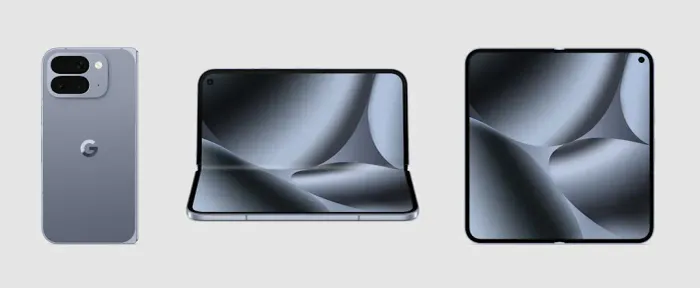

Herein lies the challenge the industry has been learning the hard way: Screens aren’t paper. They aren’t built to fold. And it’s required incredible ingenuity to change that.

I’ve been trying foldable phones since Motorola rerelased the Razr in 2019, kicking off the era of folding smartphones with a rebooted retro play. At the time, Motorola brought me into its labs to demonstrate how it had achieved the impossible. It wasn’t just another slab of electronics, but a complex mechanical device that shifted plates around to allow a ribbon of OLED screen to fold open and closed without breaking.

Motorola, alongside Samsung and Google in particular, have worked hard to expand this market while shrinking their own bulk. The companies have simplified their screens from ornate mechanical contraptions to a thin sheet of flexible glass that belies the complexity beneath (impact coatings, OLED, and hinge mechanics that prevents the screen from breaking when opened and shut).

They’ve all made incredible progress. The Pixel 10 Fold is 2mm thicker than an iPhone 17 Pro when folded. But actually 0.2mm thinner than an iPhone Air unfolded. What you may notice more is the weight, which is about 2 oz. heavier than a pro smartphone.

.

Image: Google

The Pixel 10 Pro Fold unfolds to reveal a roughly 6″x6″ screen that opens like a book. So the big question is: When you open the Fold, do you see the fold in the screen? Sometimes yes, sometimes not at all.

Head on at night in a dark room, it’s completely imperceptible. Bright white webpages are surprisingly adept at burning through any glare that might reveal geometric imperfection. The seam is most prominent if you see someone else using the Fold from the side. Most of the time, it’s subtle enough to forget about.

Obviously it’s a goal for Google to get rid of the screen fold. “Stuff that we don’t want the user to think about, to ever notice to—it needs to disappear,” says Claude Zellweger, senior director of design at Google who oversees phone hardware. But he also admits it is a somewhat “impossible task” for the engineering team.

To get closer to the impossible, Google has rebuilt its hinge to be smaller, eliminating the micro gears to have it run on tiny sliding cams (classic mechanical device that turns rotation into straight movement—kind of like a jack in the box). It helps hide the crease, but it also improves the all around proportions of the phone.

It’s all in service of Google’s somewhat ironic, ultimate goal of the product.

“We want it to feel like your regular phone,” says Zellweger.

.

Image: Google

For those moments you don’t want to unfold the Fold, there’s also a more typical touchscreen on the outside. It’s mean to feel like a “regular” touchscreen smartphone, but it still doesn’t really work that way. It’s a bit too thick, a bit too heavy.

Google insists it’s needed, especially to account for more typical smartphone behavior. In its own research, Google found most people are only spending a bit of time on their phones for most interactions, meaning unfolding it every time seemed like too much effort.

“A lot of interactions on your phone are short and fleeting. The text message that you’ve got to send to your partner quickly, the Spotify song that you need to change, the alarm that you need to set, [these tasks are done] within a minute or two,” says George Hwang, product manager at Google leading the Fold’s engineering. “And if you look at that data, those are probably like, frequency wise, about 60 to 70% of everything you do. So it’s really, really high.”

I get his point. Yet the Fold isn’t quite normal, so using it as a typical phone isn’t quite normal. The big outer screen actually ruins the occasion of using the product. I like that unfolding the phone feels intentional. It’s a certain barrier to checking your screen and getting sucked into apps. That could be a feature not a bug!

.

Image: Google

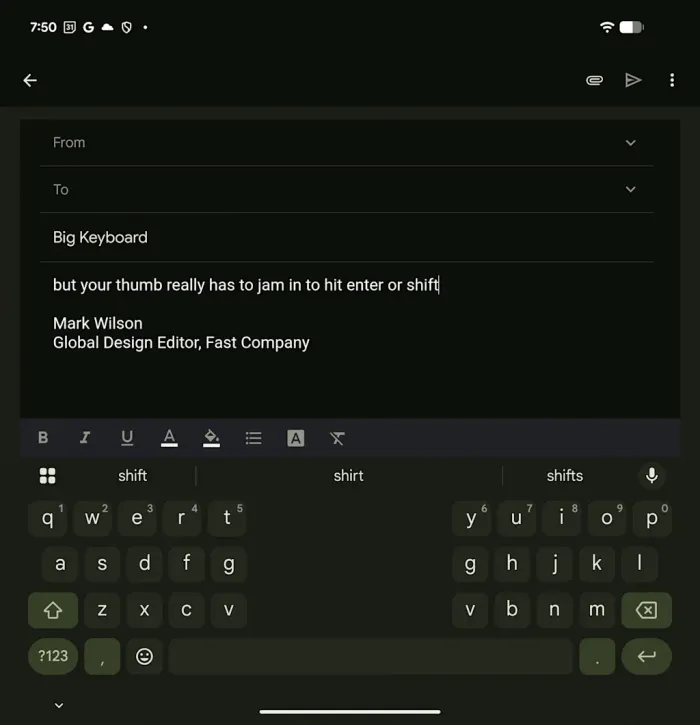

Tiny qualm, but here it is: The Pixel Fold features a split virtual keyboard for typing. It’s quite comfortable and you can type pretty darn fast on the thing. But buttons like enter are still placed way too far into the corners . . . making them a real jam of the thumb to hit.

Look, Google and everyone else—my thumbs are like Jordan’s knees. They’ve played a lot of games at this point in their career. For such a large device, users should be able to tweak the ergonomics of the keyboard to their exact preference for optimum comfort, because the screen has room. Seriously, why aren’t keyboards perfectly configured to our hand sizes in an era when my face and fingerprint unlock the phone?

At the very least, give me a few more options of the default.

Since Motorola debuted the first modern folding phone, these designs have gotten thinner, lighter, and open and close without feeling like you’re gonna break ‘em any moment.

But . . . it still feels strange to open a folding phone for the first time. It has a sort of even resistance curve that feels less like snapping open a flip phone or even opening a hard cover book than it does bending a thick coat hanger into a new shape. You actually have to open and close it a bit for the mechanisms to feel properly loosened. It’s weird!

Of course this is a small qualm in the face of some really unbelievable engineering work, but the experience of opening and closing most folding phones just doesn’t feel good enough for these products to appear solidified. It doesn’t offer a sense of innate satisfaction or completion to the action. The hardware works, but for some reason it also feels a little dead.

The Fold is getting better in this regard. It offers a light, almost “tap” sound when you open it, and a more satisfying compact-case clap when it closes. It feels good. I still want it to feel fidgety-amazing.

.

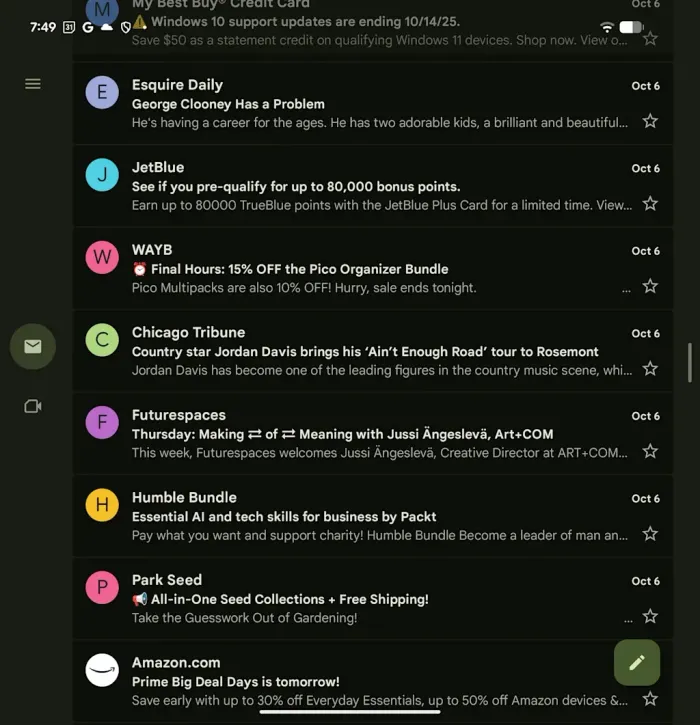

Image: Google

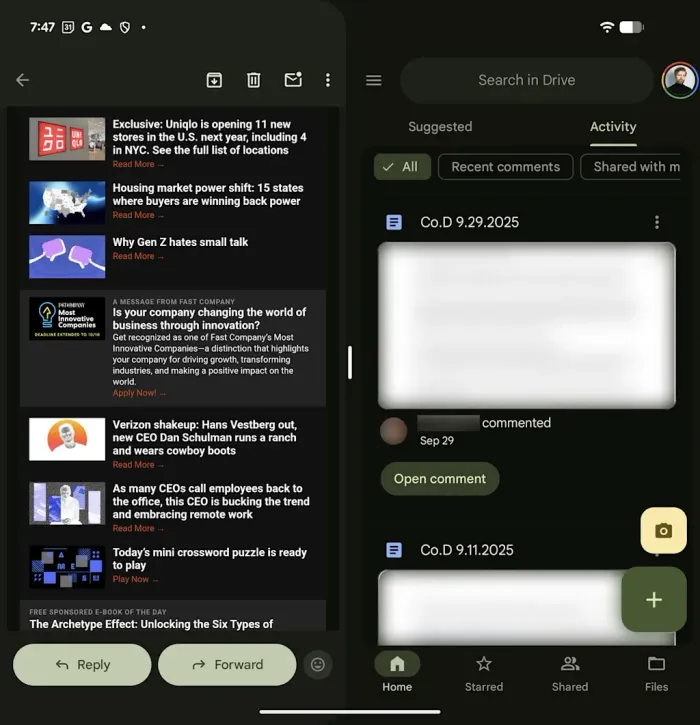

I didn’t unlock some amazing multitasking experience with the Pixel—though you can technically load two apps and, in some cases, drag and drop files between them.

Gmail feels approachable for sure, but it falls short of its potential. It formats information into either a big email or a few thin columns . . . essentially giving you the experience of holding a few phones side-by-side. It’s a sensible solution, but one that falls short of rethinking information architecture and display entirely to celebrate the possibilities of a larger screen.

.

Image: Google

But media-forward apps are a real a delight.

.

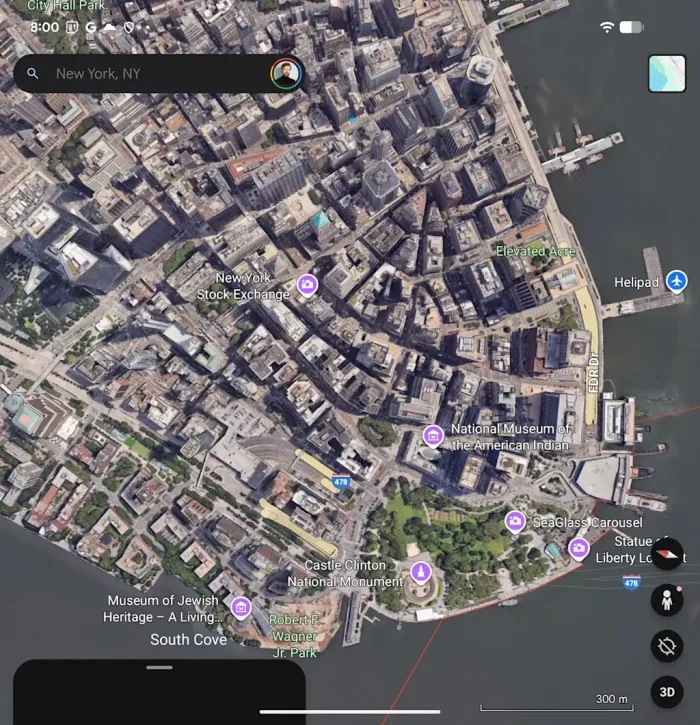

Image: Google

Instagram goes from feeling like you’re perusing large postage stamps on your regular phone, to looking at CD jewel cases on a Pixel Fold. The same is true for TikToks and YouTube clips. Yes, this sort of scale can exist on a laptop, or a tablet, of course. But the thin bezel of Google’s latest phone makes it feels almost like you’re holding this media in your hands.

.

Image: Google

It’s a unique sensation—Google Earth suddenly feels magical again. The act of holding the phone with two hands rather than one creates a preciousness to the experience—like reading a book, or using your full attention to accept a gift. It demands intention by default. I’m reminded how Zellweger was inspired by the sensation of a Moleskin when Google released its first Fold in 2023. When held open, the Fold really does feel like a precious, digital take on a notebook.

.

Image: Google

There is an ideal folding phone in all of our hearts. The Fold still isn’t quite there. It’s an engineering marvel with some very thoughtful touches of design, do not get me wrong. It’s neat as hell. It still feels a generation or two (or three?) removed from whatever sweet spot of iteration takes an idea from novel to captivating, or even essential.

Even if folding phones are the next big paradigm in smartphones, I’m not sure it means that those smartphones need to be as large as the Pixel Fold…and this 6-inch-ish crossover vehicle form the industry has landed on.

But technically speaking, can we make these phones that much smaller or thinner? Because looking at smartphones over the past decade, in many cases, we’ve actually seen them grow thicker. The iPhone Air, for all of its ingenuity, is still thicker than an iPhone 4. The industry seems cautious to make anyone give up any bit of the growing Swiss army knife of features in a modern phone.

“There is still headroom, and we’re excited about future products and things like that. On general, we’re going [pursue thinness] aggressively, but within measure, so that we don’t compromise durability and battery life,” says Zellweger.

Hwang adds that it’s easy to forget all the features we take for granted in modern smartphones, like haptics, speakers, and of course, cameras. All-in-all, these features add up to keep our phones thick. “There are subtle trade-offs when you do when you keep on pushing in [thinness] that I think most users wouldn’t know until they actually hold the device and use it side-by-side,” says Hwang, referring to these compromises as “paper cuts.”

I hope to see the entire smartphone industry push the boundaries in other ways. I want small phones like the iPhone Mini back. I want small, folding phones like the Razr back (and indeed, Motorola has been snagging some market share by offering a lower cost, smaller folding smartphone). I want curvy wearables portended by the Nike+ Fuelband back. I want to see what we can do with flexible screens outside of this smartphone-to-small-tablet size everyone seems to be investing their energies in.

“I agree with you,” says Zellweger when I present him with most of this rant. “Fundamentally, I think the extremes [in screen size] are interesting. And I think in a world where we are moving towards more sort of agentic based interactions, our need for for large displays may change.”

“Realistically, we think it’s going to change in the next five years,” adds Hwang. “And so we’re really in an interesting time to think through this stuff and be involved in it.“

Indeed. Right now, there is a unique opportunity to not just make a bunch of mostly same phones, but to push the extremes of size, shape, and ergonomics. In a sea of the regular, it’s so easy to stand out.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Mark Wilson is the global design editor at Fast Company, who covers the entirety of design’s impact on culture and business.. An authority in product design, UX, AI, experience design, retail, food, and branding, he has reported landmark features on companies ranging from Nike and Google to MSCHF, Canva, Samsung, Snap, IDEO, and Target, while profiling design luminaries including Tyler the Creator, Jony Ive, and Salehe Bembury.