.

Image: Aung Htay Hlaing

When a 7.7-magnitude earthquake hit Myanmar last year, roads buckled and thousands of buildings collapsed. But a group of small, ultra-low-cost homes made from bamboo survived without any damage.

Finished just days before the quake, the houses are emergency shelters for some of the millions of people displaced by Myanmar’s ongoing civil war. Myanmar-based architecture studio Blue Temple worked with its spinoff construction company Housing Now to make the simple prefab homes as low-cost as possible while still able to withstand natural disasters.

“We built them for the price of a smartphone—about $1,000 (R16,389) per house,” says architect and Blue Temple founder Raphaël Ascoli.

.

Image: Raphaël Ascoli

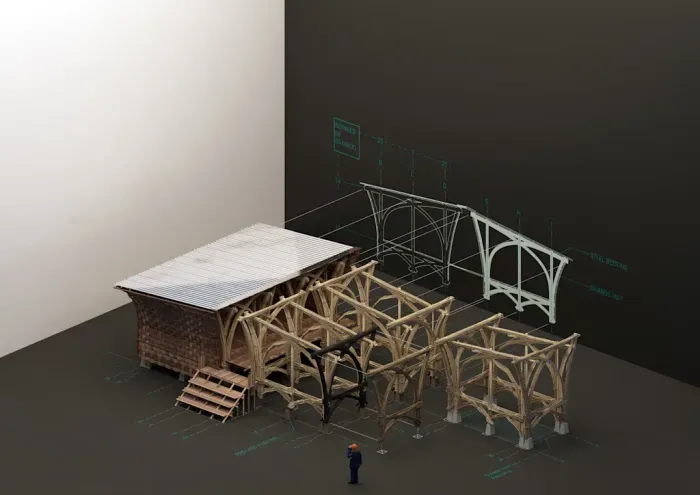

Bamboo has a long history as a construction material in the country, but the team saw an opportunity to innovate with it. Ascoli, who has been working in Myanmar for the last decade, partnered with a local bamboo carpenter on the concept.

The material is already cheaper to use than wood, concrete, or steel. But the architecture studio helped cut costs further by using a thin, low-cost species of bamboo—unlike the large species typically used in construction—and bundling it together to make it stiff and strong.

The construction company builds beams from the bamboo and then puts them together in structural frames that “we can just assemble like an Ikea kit” in less than a week, says Ascoli. “Because of the organic natural of the bamboo that we weave together into the frames, it gives the house a bit of flexibility. Instead of being very stiff and brittle like concrete, it can move a little bit.”

.

Image: Raphaël Ascoli

Any bamboo structure has some advantages in earthquakes because of its light weight and flexibility, but the company found ways to boost that performance. “We built a lot of prototypes and then pulled on them until the breaking point,” Ascoli says. “You can evaluate the maximum pressure that can be put on the house before failing.” They made tweaks to each joint to make the buildings stronger and more weatherproof.

The massive earthquake “was a real-life proof of concept,” says Ascoli. The homes, in a camp for displaced people, were less than 10 miles from the epicenter of the quake, but none of them needed repairs.

.

Image: Aung Htay Hlaing

The company has been building homes for displaced people since Myanmar’s coup in 2021. While the design can be flexible, it’s typically a simple room that residents can divide for living and sleeping; camps have separate shared bathrooms and kitchens.

.

Image: Aung Htay Hlaing

So far, the work has happened at a relatively small scale. The team is small, and funding from NGOs—which was limited to begin with—has started to disappear. When the Trump administration shut down USAID, “that had massive consequences on the humanitarian response in Myanmar,” says Ascoli. “A lot of NGOs are now closing down and unable to continue operating.” Other countries have also cut funding. There’s also a shortage of construction labor because of the war.

.

Image: Aung Htay Hlaing

To keep going, the team is experimenting with new approaches. “If we want to scale, we have to be radical,” he says. The latest project, developed over the last 18 months, is a DIY construction manual that helps citizens incorporate some of the design team’s techniques to optimise bamboo construction as they build homes themselves.

“The humanitarian sector is kind of failing at the moment because it’s relying on unreliable sources of funding, and it’s an archaic system,” says Ascoli. “We’re basically trying to test out if there is an alternative to traditional humanitarian response, and trying to find what can be the post-NGO humanitarian response programs that will replace the old systems.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Adele Peters is a senior writer at Fast Company who focuses on solutions to climate change and other global challenges, interviewing leaders from Al Gore and Bill Gates to emerging climate tech entrepreneurs like Mary Yap.. She contributed to the bestselling book Worldchanging: A User's Guide for the 21st Century and a new book from Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies called State of Housing Design 2023.