.

Image: Fujifilm

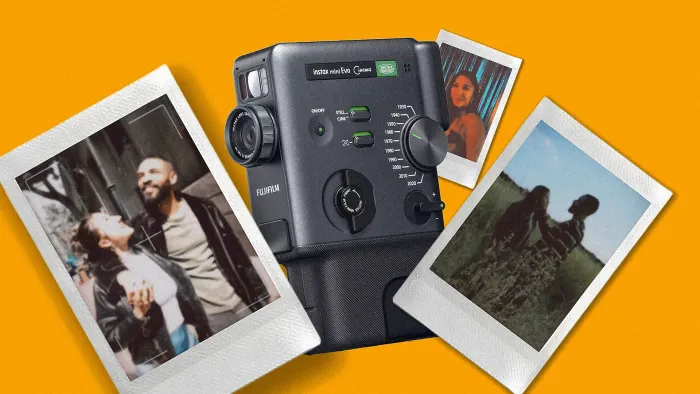

Fujifilm’s newest camera model, the Instax Mini Evo Cinema, is a gadget that’s designed for the retro camera craze.

The device is a vertically oriented instant camera that can take still images, videos (an Instax camera first), connect with your smartphone to turn its photos into physical prints, and capture images in a wide range of retro aesthetics. It’s debuting in North American markets in early February for $409.95.

Fujifilm’s new model taps into a younger consumer base’s growing interest both in retro tech and film photography aesthetics—a trend that’s been driven, in large part, by platforms like TikTok. The Instax Mini Evo Cinema turns that niche into a clever feature called the “Gen Dial”: a literal dial that lets users toggle between decades to capture their perfect retro shot.

.

Image: Fujifilm

Almost everything about the Instax Mini Evo Cinema screams nostalgia, from its satisfying tactile buttons to its vertical orientation—and that’s by design.

According to Fujifilm, the camera’s silhouette is inspired by the 1965 Fujica Single-8, an 8-millimeter camera initially introduced as an alternative to Kodak’s Super 8. While the Instax Mini Evo Cinema does come with a small LCD display, its main functions are controlled with a series of dials, buttons, and switches, which Fujifilm says are designed “to evoke the feel of winding film by hand, add to the analog charm, and expand the joy of shooting and printing.”

The most innovative of these is undoubtedly the Gen Dial. While there are plenty of existing editing apps and filter presets to give a photo a certain vintage look in-post, this may be the first instant camera to actually brand in-camera filters by era.

.

Image: Fujifilm

The dial is labeled in 10-year increments, from 1930 to 2020. To choose an effect, users can simply click to the era they’d like to replicate, then shoot and print. According to the company, selecting “1940” will result in a look inspired by the “vivid color expression of the three-color film processes,” for example; 1980 pulls cues from 35-millimeter color negative film; and 2010 evokes the style of early smartphone photo-editing apps (throwback!).

“Overall, our goal with Mini Evo Cinema is to deepen options for creative expression,” says Ashley Reeder Morgan, VP of consumer products for Fujifilm’s North America division. “Beyond video, the Gen Dial provides an experience to transcend time and space over 100 years (10 eras), applying both visual and audio to the mini Evo Cinema output.”

From left: 1940, 1980, and 2010 styles

Image: Fujifilm

For amateur photographers looking to achieve a certain vintage aesthetic without spending endless hours in Adobe Lightroom or fiddling with complicated camera settings, it’s the perfect intuitive solution.

For Fujifilm, the Instax Mini Evo Cinema is part of a broader, internet-driven revival of the brand’s camera division.

While Fujifilm previously spent years moving away from its legacy camera business to focus on healthcare, its $1,599 retro-themed X100V camera—which went viral on TikTok—recently triggered a resurgence in its sales. The company’s most recent financials, released in September, show that its imaging division (which includes cameras) experienced a 15.6% revenue increase year over year, which Morgan says is attributable to the success of its instant and digital cameras.

“Overall, we have been thrilled to see younger generations rediscovering the joy of photography, whether instant, analog, or digital,” Morgan says.

The X100V’s popularity online is likely driven by Gen Z and Gen Alpha’s interest in retro tech aesthetics (see: Urban Outfitter’s iPod revival), as well as a more general resurgence in film photography in recent years. Analog cameras are having a moment, and companies like Polaroid and Fujifilm are cashing in.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Grace Snelling is an editorial assistant for Fast Company with a focus on product design, branding, art, and all things Gen Z. Her stories have included an exploration into the wacky world of Duolingo’s famous mascot, an interview with the New Yorker’s art editor about the scramble to prepare a cover image of Donald Trump post-2024 election, and an analysis of how the pineapple became the ultimate sex symbol

FAST COMPANY