.

Image: FC

As I uploaded a 1940s photo of my grandpa Max and hit a few buttons in Google’s Veo 3 video generator, I saw a familiar family photo transform from black and white to colour.

Then, my grandpa stepped out of the photo and walked confidently toward the camera, his army uniform perfectly pressed as his arms swung at the sides of his lanky frame.

This is the kind of thing AI lets you do now—virtually bring back the dead.

As a hilarious Saturday Night Live sketch this weekend highlighted, though, just because we can reanimate our departed loved ones, that doesn’t necessarily mean we should.

The sketch, which The Atlantic has already called SNL’s “Black Mirror Moment”, features Ashley Padilla as an aging grandmother in a nursing home.

Her family members—played by Sarah Sherman and Marcello Hernández—visit her on Thanksgiving, and use an AI photo app to bring her old family photos to life as short videos.

At first, things go well. Padilla’s character marvels over a black and white image of her father waving as he stands in front of a spinning ferris wheel.

But then, things go hilariously, predictably wrong. A photo of family members at a barbecue turns into a horror scene when the fictional AI app has Padilla’s father (played by host Glen Powell) roast the family dog, which happens to have no head.

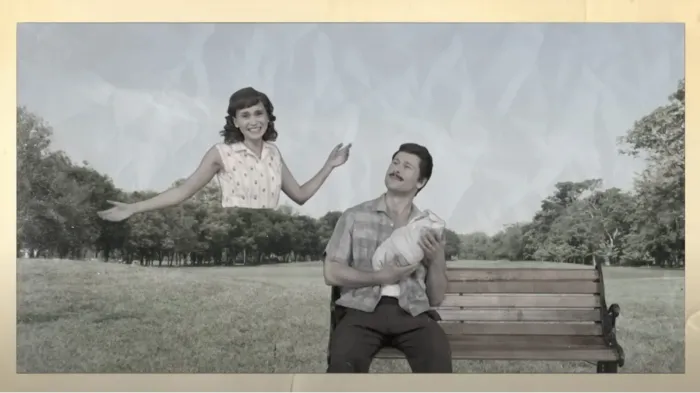

As other photos come to life, Padilla’s father pays a bowling buddy to perform a lewd act, and in a baby photo, her mother’s torso splits from her body and floats around the frame as a nuclear bomb explodes in the background.

The sketch is hilarious because it’s so relatable. Anyone who has played with AI video generators knows that they can make delightfully wonky assumptions about the laws of physics—often with spectacular results.

In my testing of AI video generator RunwayML, for example, I asked the model to create a video of a playful kitten at sunset.

Things start out cute enough, until the kitten splits in two, with its front half attempting to exit stage right as its back half continues adorably cavorting around.

Video generators make these errors because of the way they’re trained. Whereas a text-based AI model can learn by reading essentially every book, website, and other piece of textual data ever published, the amount of training-ready video content is far more limited.

Most AI video generators train on videos from social media platforms like YouTube. That means they’re great at creating the kinds of videos that often appear on those platforms.

As I’ve demonstrated before, if you want people knocking over wedding cakes or having heated arguments with their roommates, video generators like Veo and Sora excel at making them.

For less commonly posted scenes, though, the available training data is far more limited.

Most online videos, for example, show interesting things happening. People rarely post hour-long clips of themselves casually walking around (or to SNL’s example, holding a baby or grilling a hot dog) on YouTube or Instagram.

Those videos would be so terminally boring that no person would want to watch them. Yet copious amounts of video of these kinds of boring, everyday activities are exactly what AI companies need to properly train their video generators.

This has created a fascinating market for such clips. Companies like Waffle Video are popping up to serve the need, paying creators to film themselves doing things like chopping vegetables or writing specific words on pieces of paper for AI training.

Until AI companies can get their hands on more videos of these kinds of mundane actions, though, AI video generators will struggle to mimic them.

Ironically, video generators are currently great at showing fanciful, dramatic actions. Ask them to make the kinds of everyday scenes you might find in an old black and white family photo, though, and you get Fido on the barbie.

All that brings us to the question: should you use today’s AI tools to reanimate your dead loved ones?

My best advice: Wait a bit.

AI video tech is advancing incredibly quickly. The first tools that added movement to family photos—like Deep Nostalgia from My Heritage, which launched in 2021—used machine learning to perform their wizardry.

The tech felt revolutionary at the time. Today, it looks primitive compared to the full motion scenes like the one of my Veo-animated grandpa.

And even with those advances, Veo and its ilk are still in their avocado chair moment.

Image generators have improved tremendously as their creators have gotten better at training them. Video generators will see similarly vast improvements—especially as AI companies invest millions in buying bespoke training data of everyday movements.

Personally, I brought a photo of my grandpa to life because I thought the real Grandpa Max would find it amusing. I’ve resisted reanimating photos of more recently departed loved ones, though, for many of the reasons implicit in SNL’s sketch.

Family photos are intimate things. It’s nice to see your late loved one smile and wave at you. Seeing them split in two or explode in a nuclear fireball, though, would be disturbing—and something you couldn’t unsee once you’ve conjured it up from the depths of Sora or Veo’s silicon brain.

Until AI models can be trusted to avoid these kinds of distributing, random visual detours, we shouldn’t trust them with our most prized memories.

A splitting kitten is amusing. A splitting grandma, less so.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Thomas Smith is a Johns Hopkins-trained artificial intelligence expert and journalist with 15 years of experience. Smith was hailed as a "veteran programmer" by the New York Times for his work with human-in-the-loop AI, served as an Open AI Beta tester, and has led the AI-driven photography agency Gado Images as Co-Founder/CEO for 12 years.