.

Image: Walter_D/Adobe Stock]

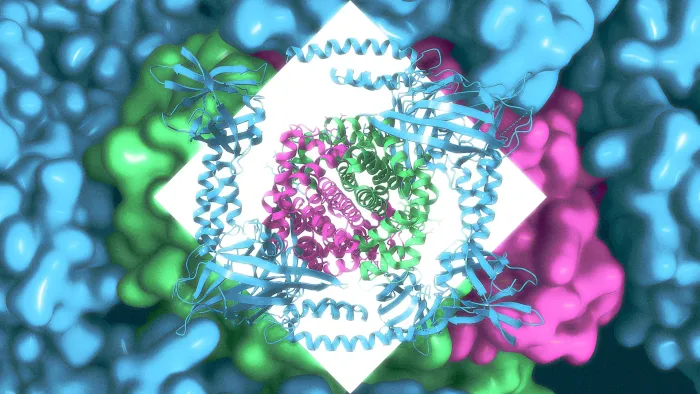

Inside a lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology late last year, scientists gave an AI system a new task: designing entirely new molecules for potential antibiotics from scratch. Within a day or two—following a few months of training—the algorithms had generated more than 29 million new molecules, unlike any that existed before.

Traditional drug discovery is a slow, painstaking process. But AI is beginning to transform it. At MIT, the research is aimed at the growing challenge of antibiotic-resistant infections, which kill more than a million people globally each year. Existing antibiotics haven’t kept up with the threat.

“The number of resistant bacterial pathogens has been growing, decade upon decade,” says James Collins, a professor of medical engineering at MIT. “And the number of new antibiotics being developed has been dropping, decade upon decade.” The research, recently published in the journal Cell, is part of his lab’s Antibiotics-AI Project and offers one example of AI’s potential in medicine.

The team tried making a small number of the compounds, and then used one to clear a drug-resistant infection in a mouse. In another part of the study, the researchers used a different approach to generate additional molecules, leading to another successful test in mice—and the possibility that novel, fully AI-designed drugs may eventually be available for the most dangerous infections.

.

Image: Walter_D/Adobe Stock

The standard approach to creating new antibiotics involves screening an existing library of compounds, one by one, or sifting through samples of soil to find promising new candidates.

Since the 1980s, the Food and Drug Administration has approved a few dozen new antibiotics, but most of them are minor variations on drugs that already exist.

“What’s happened in the last couple decades is, it’s largely been a discovery gap where folks are discovering antibiotics, but they’re more or less very similar—and they are analogs to existing antibiotics,” Collins says.

The challenge is compounded by poor economics for drug companies. “It costs effectively just as much to develop an antibiotic as it does a cancer drug or blood pressure drug, for example,” he says. “With an antibiotic, you might only take it once or only over a few days, whereas with a cancer drug or a blood pressure drug, you could take it for many months, years, or even for the rest of your life. With each use, an antibiotic also only makes a fraction of the profit.”

All of this means that if you’re infected with bacteria that’s hard to treat—like methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), which also resists many other drugs—there are fewer options available. In the U.S., MRSA kills an estimated 9,000 people each year.

.

Image: Walter_D/Adobe Stock

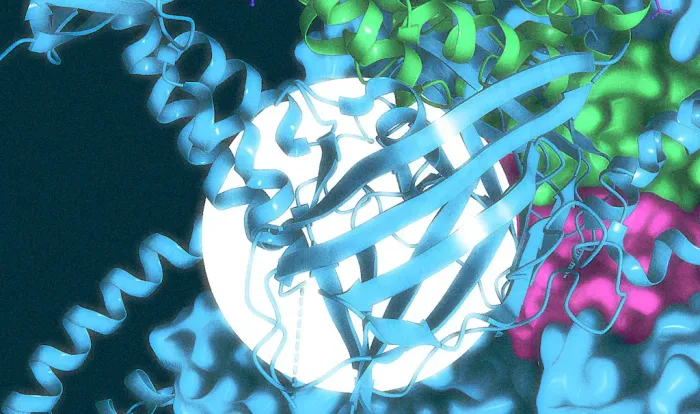

The Collins Lab has been studying antibiotics for around 20 years. Initially, the team used machine learning to better understand how antibiotics work and to look for ways to make existing antibiotics more effective. Around six years ago, they started using artificial intelligence as a platform for antibiotic discovery.

They used AI to screen existing libraries of compounds to look for new antibiotics, leading to the discovery of new molecules that worked against infections in new ways. A spin-off nonprofit, Phare Bio, is now working to move promising candidates toward the market. The biotech company hopes to launch a trial of halicin, a drug initially developed for diabetes treatment in 2009 that was discovered to have powerful antibiotic properties by Collins’s research team a decade later.

The latest research goes a step further—not just screening through existing compounds, but creating new ones. The scientists used two different approaches. First, they used a library of millions of chemical fragments known to have antimicrobial activity, and used the algorithms to turn those fragments into complete molecules.

In the second approach, they used the AI to freely design new molecules, without starting from existing fragments. As the computer churned through new designs, the researchers were free to work on other tasks until the AI was done.

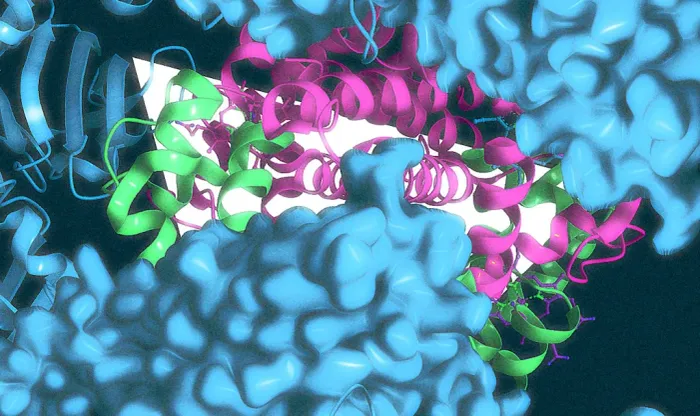

After the molecules were generated, “we applied a series of down-selection filters to prioritize which ones to synthesize and test,” says Aarti Krishnan, a senior postdoctoral fellow in the lab. “Those steps took a few days and involved human feedback, where medicinal chemists manually inspected over 5,000 candidate molecules and selected them for synthesizability.”

Actually making the molecules was challenging—some of the AI’s ideas were so wild that they would either be impossible or impractical to manufacture. (This will improve as the AI evolves.) But the team was able to make a small number. From the part of the study that worked from fragments of existing molecules, the scientists were able to make two candidates, one of which was very effective at killing drug-resistant gonorrhea bacteria.

From the part of the study that let AI freely design new molecules, they synthesized and tested 22 samples, ultimately advancing one candidate in a successful test that treated drug-resistant MRSA in mice. Now, the lab’s nonprofit partner is continuing to work on both molecules so they can undergo more testing.

.

Image: Walter_D/Adobe Stock

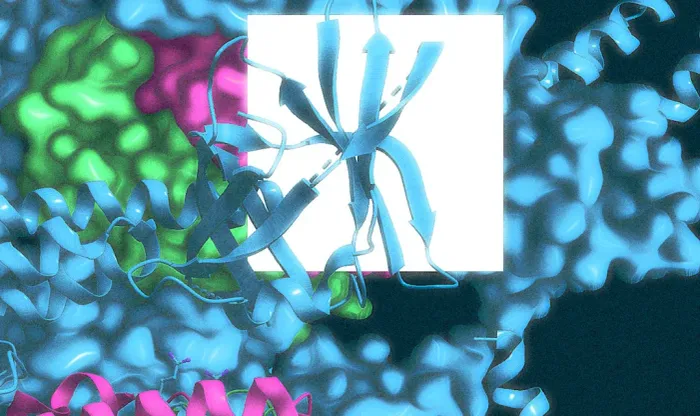

While the use of AI in drug development isn’t new, this particular application of generative AI is. “To our knowledge, this is the first generative-AI approach that’s designed completely novel antibiotic candidates whose structures do not exist in any commercial vendor space,” Krishnan says.

Drug development is still a slow process, and moving through human trials will continue to take time. But AI can clearly help in the early discovery phase, reducing cost and increasing the chances of success. “AI allowed us to explore much larger chemical spaces than are currently available from screening libraries. And in doing so, it opened up these new molecules for our consideration,” Collins says.

The approach could also be useful for other types of medicine. “All of the AI methods that we use could be readily extended to other indications,” he says.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Adele Peters is a senior writer at Fast Company who focuses on solutions to climate change and other global challenges, interviewing leaders from Al Gore and Bill Gates to emerging climate tech entrepreneurs like Mary Yap.. She contributed to the bestselling book Worldchanging: A User's Guide for the 21st Century and a new book from Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies called State of Housing Design 2023.